From a 2008 graduate to all the 2020 graduates – don’t lose hope.

Dublin port, July, 13th 2008, 4:30am-ish, my trek from Nottingham (UK) is finishing. 6 days ago, I was defending my master’s thesis in employment law in Bordeaux, before returning to England were the rent was paid in my student accommodation for another month.

By that stage, I had been looking for and applying for jobs every morning for 2 hours since April. I had had countless interviews and even got an offer (to this day, I’m still waiting for the contract or any kind of update). Since I speak English and French, I applied in the European countries that spoke these languages: France (obviously), Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, the UK and Ireland. For some unknown reason, I was getting interviews in Ireland, more than anywhere else. So, out of sheer desperation, I moved over to Dublin.

With the global lock-down in spring 2020, you read a lot of articles that talk about the “sacrificed generation”. Allegedly, the various governments of the world sacrificed a full generation’s future career to prevent more deaths in the older generations. As someone who graduated in the pit of a recession caused by greedy banks, I think it’s a bit of a stretch to say that we tanked the economy without any regards for the generation that is graduating and entering the job market. Let’s put that into context; we know that Covid-19 kills 1% of the infected people, that 20% of the infected cases will need to be hospitalised and that pre-lock-down, the R0 was up to 5 (which is considerably lower than the R0 of the measles at 15 to 20, but still). I looked at the numbers of “confirmed cases” pre-lock-down and tried to work out the math on a planetary scale (about 7 billion people). I stopped; the volume scared the sh*t out of me. At the time I’m writing, we’re now at roughly 572 000 deaths across the world - that’s over half a million people dead. Half a million. Let that sink in for a second. Right, so let’s now forget all thoughts of the lock-downs sacrificing the graduates, because the economy would have tanked under the pandemic anyway under the sheer number of people sick and dead.

Going back to what it’s like to graduate when the sh* has hit the fan. After I moved to Dublin, it took me 3 weeks to get a job. At that point, I was handing my CV in every shop, restaurant and fast-food place that would take it as well as applying to any legal secretaries, assistant, French speaking job that I could find on the internet. By that time, I was a pro at the internet job search, I had a document with every job that I had applied for, and I knew that most places posted their new jobs on Tuesdays in Ireland (I can’t remember the other countries, it was a while back, but I had trends for all my target countries).

I remember vividly being told by the manager of McDonald's that he wouldn’t take my CV because with a master’s degree in law, I was overqualified. So, I removed my master from my CV when applying restaurant jobs.

Two weeks of full-time job search later, I had brought in my typing speed to the required number of words per minute, I had bought a book and taught myself Excel, every single agency in Dublin had my CV (Hello GDPR emails by the boatload in May 2018) and depression was rearing its ugly head. Should have I stayed in France in 2007 and prepared for the Civil Services competitive exams instead of doing a masters’ degree? How could I suck so much at interviews that I couldn’t get a job as a waitress or even a reply after phone interviews? And that’s not even including the concerned family and friends asking “what are you going to do?”.

Looking back, the amount of stress I was under was insane. Going back to France and living with my parents was not a possibility, so I didn’t have that safety net. I couldn’t apply for social welfare payments as a graduate in any country. My only option was to get a job. Any job.

And then one Wednesday morning, after a sleepless night, the phone rang. Could I take a 2 hours online translating test today? I had a laptop but no internet, so I opted for going to the internet café where I was a regular (one cannot always be searching for a job using the McDonald’s free wifi). About 10 minutes into the test, a guy started playing the accordion right by the door, the word doc was in English, so it kept auto-changing the spelling of some words while I was saving the doc. Proofread, change spelling, save. Proofread again, damn it, why is there 2 g in that word, change, save. I didn’t really think I did a good job on that test. And yet, the next morning, I got a call, could I come and meet the recruiter in town. So off I went, suited and booted to meet a recruiter in what seem like a corridor. Literally a small table, 2 chairs and people walking by. I had an interview the next morning for a 3 months fixed term contract as a localisation translator for a video game with a salary of €12 per hour. Did it sound like my dream job? Let’s face it, no. But if I got the job, it would pay the rent and give me 3 months to find another job.

Turns out I had done a good job on the test, and the company wanted to meet me the next morning (Friday). I had done what research I could on a game that wasn’t released yet, and I was prepared to talk about my tiny translation experience (a student job, translating a series of psychological test for a grad student) in English. The interview was in French, and I had left an extra g on my test, and I was suited and booted when everyone (including the guy that was waiting for his own interview beside me in the lobby) was wearing jeans and hoodies. I was sure I had bombed the interview, yet again, when I called the recruiter to let her know and she seemed disappointed that I wasn’t given an offer on the spot since the job had a start date the next Monday.

I remember the feeling of absolute despair I felt as I crossed St Stephen’s Green on my way home.

Obviously, my story has a happy ending, otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about it now. I waited for a call from the agency all day, and at 4:45pm, I set off to the local Tesco for groceries, thinking that everything was lost; if I was ever to get an offer, it would have come by now. And then the call came, and there I was literally jumping up and down on the street, agreeing to start on Monday without a contract because it was too late in the day, but at that point, I couldn’t care less about the terms and conditions of my employment. 3 months, €12 per hour, sure, I’ll take it!

I started that Monday as a video games translator – without having played a single video games in my life (parental decree). I gave that job everything that I had, and I became good at it. I built relationships with people in various teams as I was asking for more information to help with my translations. I learnt to cope with the weird habits of co-workers (my desk neighbour was trimming her nails at her desk, every day) and the rants of various managers (hello you IT manager who raged at me because my co-worker didn’t lock his PC, to this day, I always lock my PC).

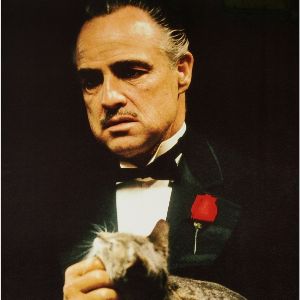

I would probably still be working in localisation if… I had not been made redundant in July 2009. It was still the recession, I had not been able to secure a better job in the 12 months I had been working, and I went back to applying for jobs in multiple countries. I remember interviewing for a sales job, and the 1st interview question was: Do you like my poster?

Credits: The Godfather - Copola

In hindsight, if your potential future boss has a poster of The Godfather in

his office, that might be a red flag, but I was too naïve to know I got the

job, but ended up not taking it as I got an HR job in Paris.

A permanent HR job. Grand-mother was over the moon. Finally, a job that was 1°) permanent and 2°) within the field that I had studied.

Turns out that I hated that job with a passion. I had replaced someone who had been in that job for 37 years (yes, her entire career in that exact job), her butt was imprinted into the chair’s cushion, both literally and figuratively. The salary barely paid the rent, the taxes and the public transports, but I stuck to that job for 12 months. Long enough to get decent experience on my CV and to secure another job…in Dublin.

This is my story, as a graduate and a recent graduate looking for a job during the World Financial Crisis. It was hard, stressful, disheartening. I learnt that a degree means nothing when it comes to getting a job (although, not having a degree could be a deal breaker), that you might do a decent interview and yet never get a call back, that you can get a job offer and never get a contract, that salary expectations are not in line with your level of education but on your level of experience and that you can’t hide behind the economic crisis. You just have to keep trying your best, even when your best is not good enough (thanks University for teaching me that).

What you will gain from that experience:

- A lot of weird coping mechanisms

- Flexibility

- Interviewing practice

- Resilience

All of which are very good skills to have on the job market.

Good luck!